After a week of wandering around northern Greece, I realize, once again, that this kind of road trip has a fantastic charm. Overlooking the gradually accumulating fatigue that a top physical condition can beat, the experiences that unfold continuously, including people, places, and activities, fall into the category of things you would take with you to a desert island of existence to repeat in another life.

So, I leave Pieria and the gods of Mount Olympus behind and head, in the evening watch, to Epirus, the region of north-western Greece. To avoid doubt, I’ll anticipate a little by saying at the outset that Epirus – leaving aside the islands and the rest of the well-known coastal areas – is the most beautiful region in Greece. In fact, I’d even include it in a European top for scenery and diversity of relief, its two sub-regions – Tzoumerka and Zagori – having everything you could want to include in a delicious tourist cocktail. That means, below, you will read about what to see and do in Epirus, Greece. And what are the best tourist attractions of Epirus.

Find your best flight to Greece!

Map with the main tourist attractions in Epirus (zoom for details)

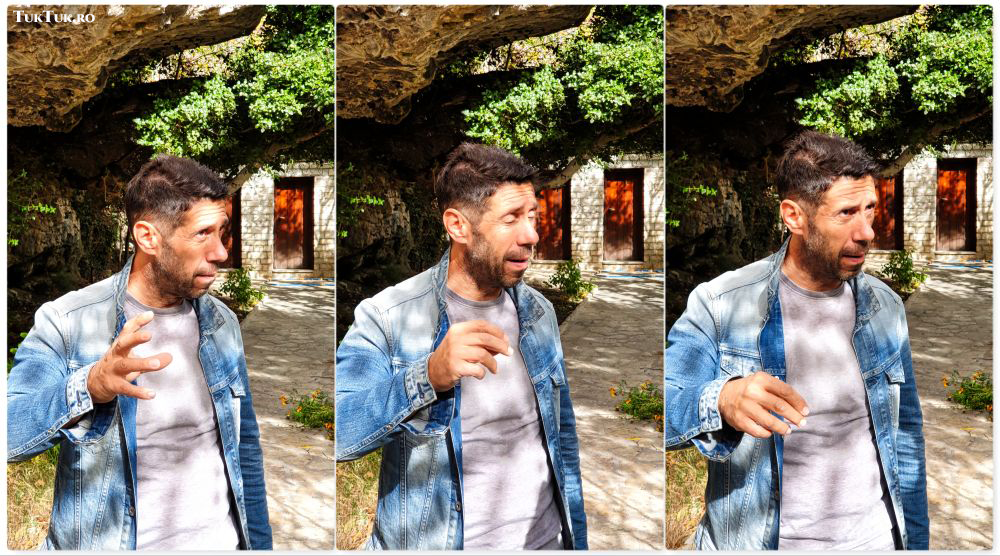

Before long, with my batteries drained, I throw myself into bed at the Anavasi Mountain Resort in the village of Tsopelas, only to wake up the next day to the mountains banging on my window, almost screaming at me to get acquainted sooner. Nothing could be easier, especially since I had already met Achilles Papaefthimiou, our friendly Epirus guide, a character who looks like something out of a Jules Verne story, ready to take you to the center of the Earth with a smile on his lips and a zen in his eyes, no matter what dangers loom on the horizon. Achilles is a Vlach, and that’s one reason to realize that in Epirus, we are in Vlach ‘territory’, the region of the Aromanians.

Most Vlachs live in northern Greece, in pastoral communities scattered through villages in the Pindus and Meglan mountains, around Lake Prespa, and a little further afield in Olympus and Vermion. The Vlach minority is arguably the most integrated of the minorities in this country, with Greeks referring to them as “Greeks speaking a strange dialect.” I won’t go into the sometimes sensitive discussion here, but before visiting Epirus, it is worth knowing a few brief details about the history of the Vlachs.

Of uncertain descent (Roman legions or the pre-Roman population, later Latinised), in the early Middle Ages, the Vlachs formed small, independent, and fairly powerful kingdoms; by the 11th century, these communities of shepherds were mentioned as transhumance in winter to the plains of Thessaly and returning in summer to the Pindus Mountains. Later, under the rule of the Ottoman Empire, the Vlachs supported the political and cultural causes of the Greeks, playing an essential role in gaining the country’s independence. Some Vlachs (especially those from Macedonia) were attracted to Romania, migrating to the territory of Valachia and forming the Aromanian communities that we know even today. Romanians founded schools for the Vlachs in Macedonia, and after the 1913 treaty, these schools were allowed to operate on Greek territory. After the Second World War, the Romanian state did not support Vlach schools and churches.

So there is a historical (and not only) link between the Romanians and the Vlachs. Achilles says he understands many Romanian words, exemplified in abundance on the way to the first goal in the Tzoumerka sub-region: the Kipinas Monastery.

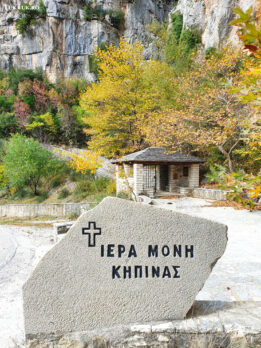

Kipinas, the monastery with the cave in the altar

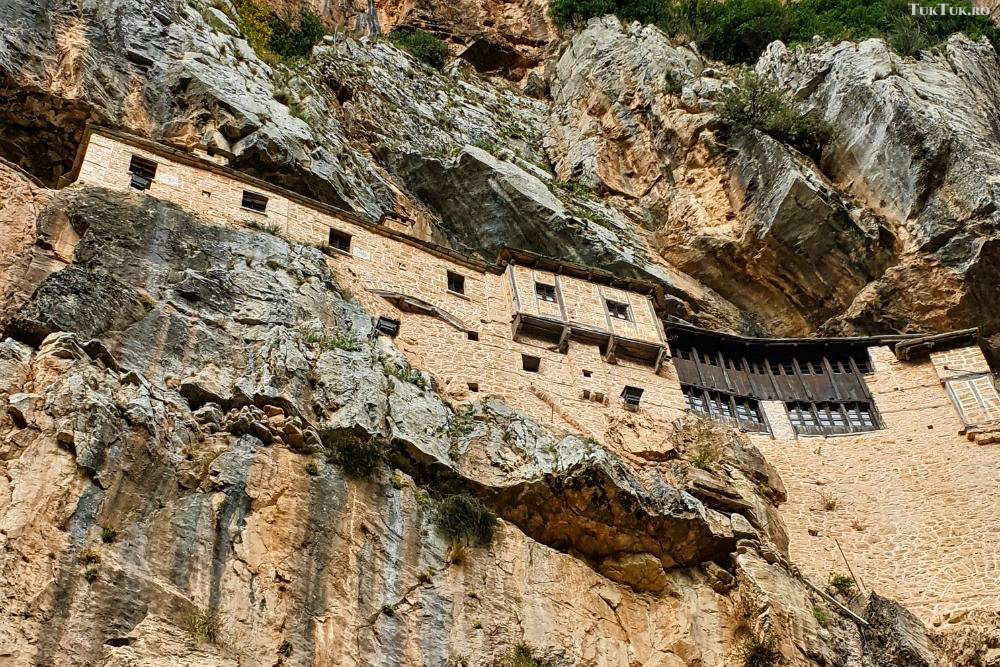

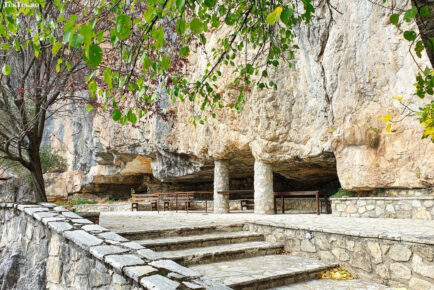

I’m not necessarily a fan of ecumenical tourism, but there are some monasteries for which it’s good to thank God for bringing them your way. And that’s because they transcend the barriers of ‘normality,’ being built in unexpected places and bizarre shapes. Kipinas Monastery can easily fall into this category.

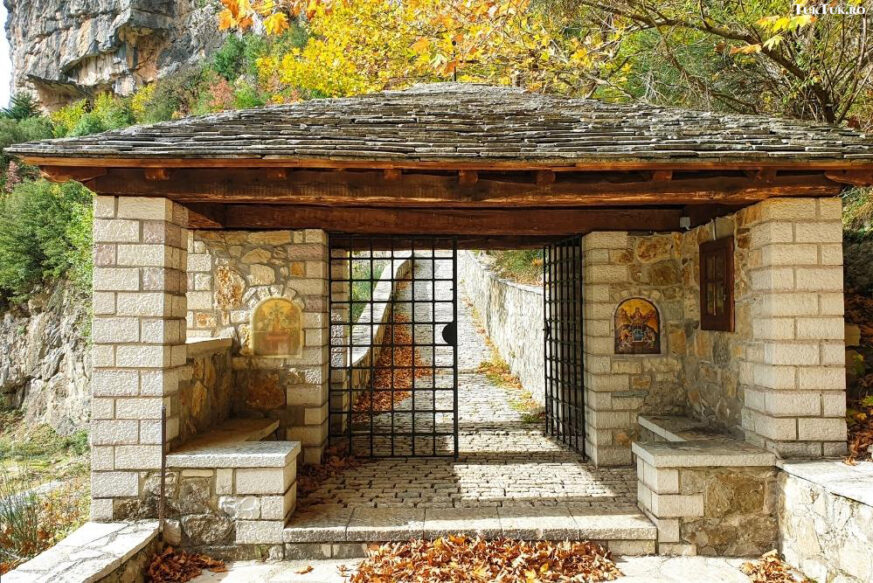

Located in the gorge of the Kalarytikos River in the Tzoumerka Mountains (near the village of Kalarites), Kipinas is a monastery carved into the rock at a considerable height. Monks do not inhabit it, so if you want to visit it, you need to know the secret: the key should be taken from the neighboring village (and brought back at the end of the visit). If you happen to be there at a quiet time, chances are that in the half hour you set aside to admire this gem, you’ll have a fantastic exclusive.

After leaving your car in the small car park at the bottom, you climb the path up to the cliff where the monastery was “carved” and open the wooden gate to enter the clean and quiet interior. Kipinas was built in 1212 by a group of monks who broke away from the neighboring Vyliza Monastery following disagreements with the abbot. They settled in a cave they discovered by chance and began to build a monastery-like entrance using materials from the surrounding area.

At that time, the great danger to any church establishment was raided by robbers. The monks, skilled men, built a high, protective wall, a strong door, and a swinging wooden bridge, which they pulled up when they felt the raiders approaching. Between the 14th and 19th centuries, the monastery played another significant role: because the cave in which it was built extended 240 meters into the cliff, it served as a hiding place for the Greeks from Ottoman attacks.

Incidentally, I immediately located the door leading to the cave, which you can enter without any problems, walking a few meters and putting yourself in the position of a Greek threatened by Turkish rage. It’s not exactly the most comfortable place to spend your days, but in those dark ages of humanity, 5-star bunkers didn’t appear.

The few rooms of the little monastery are in perfect order and cleanliness, which shows that the place is under constant management. There is also a restroom, under lock and key, which I could peek into through the crack in the door. You can buy (and light) candles, self-serve with small religious items or souvenirs, leave your money next door, and study the 17th-century painted frescoes and handmade furniture. And, of course, you can enjoy the view of the gorge from high above, thinking of the soul’s immortality and times of peace. The Kipinas Monastery is a special place that is bound to stay with you.

With the holy in our hearts and fresh air in our lungs, guided by the brave and skilled Achilles, we quickly make our way to one of Epirus’ ‘hidden’ places, a short distance from Kipinas. Northern Greece is full of waterfalls, some more beautiful than others. A few minutes from the village of Kalarites, we leave the car in a car park, cross a metal bridge over the Kalarritikos river, come to an old mill turned café (closed in November) and walk for ten minutes along a path until we come across the Kouiassa waterfall, beautifully embedded in the forest landscape.

If only the temperature were a little warmer, you’d almost want to dip your feet in the crystal-clear water the little waterfall gleefully pours through the boulders scattered all around. But as we won’t have this privilege for a few months, we’re making our way back from the forest to the countryside. Because eternity was born in the countryside, right? And Greece’s ‘countryside’ is no exception.

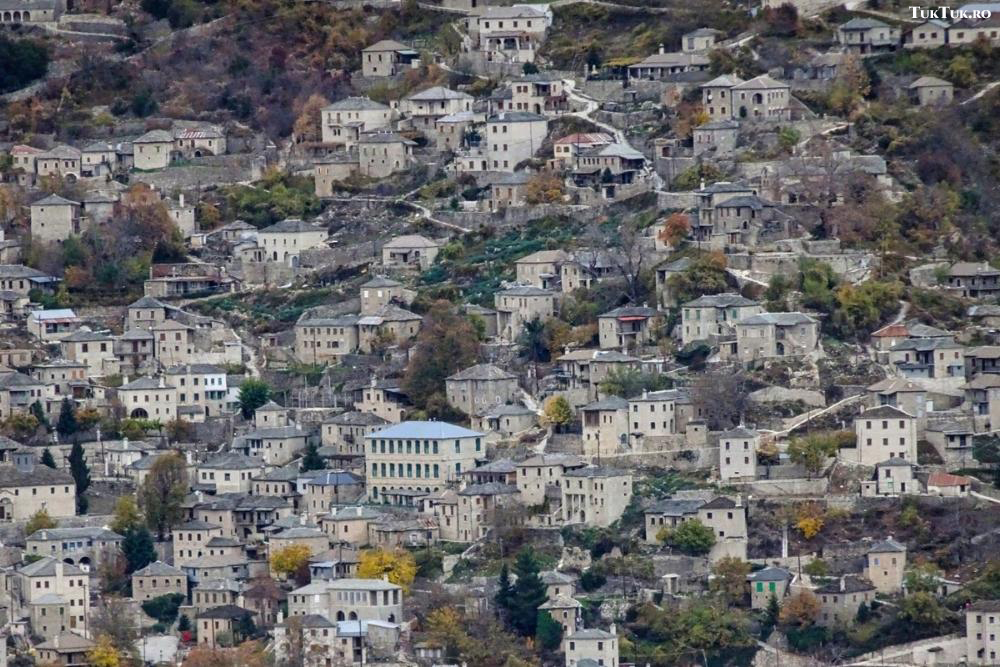

The village of Kalarites, Napoleon’s songs, and the… rebetiko concert

Kalarites and Sirrako are two neighboring and almost identical villages, linked by a 2.5 km long path. Both have houses built of stone by local craftsmen; these are set on the hill like a huge amphitheater. The villages are mentioned in the notes of French explorers in 1815, who described them as developed settlements with intellectual life and even a library. They had a hard time with the Turks, who, before the Greek Revolution, set fire to them to block the road linking Thesally and Ioannina, but they later revived like the phoenix after the liberation of Epirus.

Two orange cats line up next to a cheerful dog, looking like the perfect punching bag for rural feline antics. Time seems to be on standby in the village of Kalarites, a traditional Vlach village in the Tzoumerka Mountains at 1200 meters.

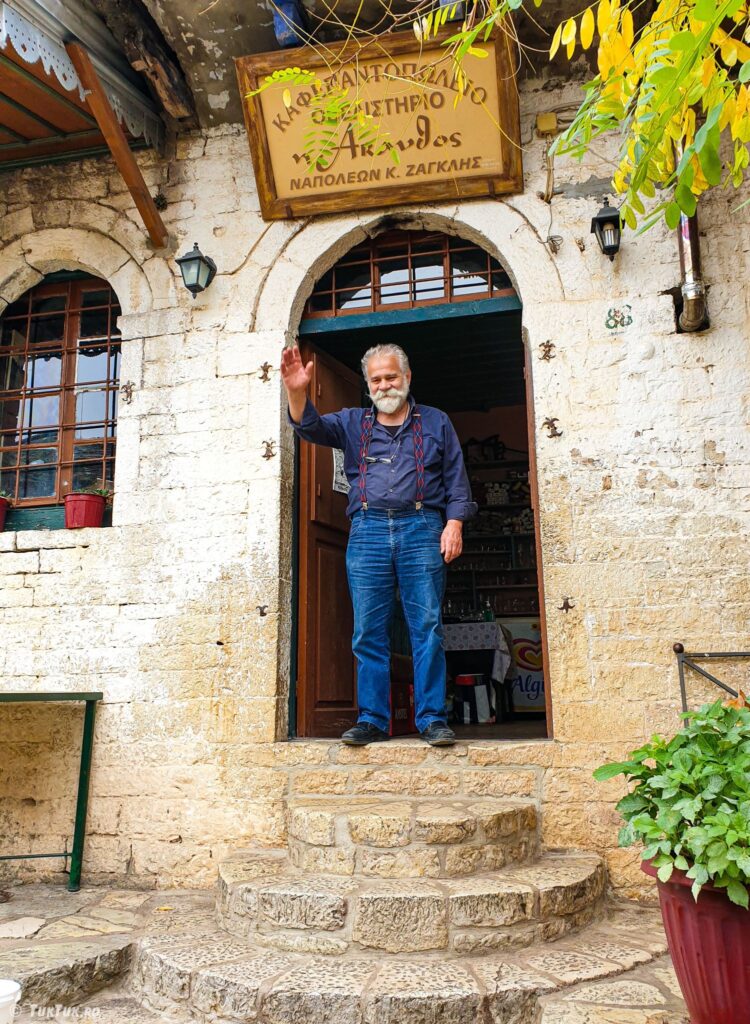

No one is on the cobbled lanes, with houses from early 20th-century photographs. I enter the door of the Akanthos café and am struck by an image from an old film. A charming old actor figure suddenly appears: Napoleon, the owner, is an Aromanian. With all that goes with it, including the words that screw (a)Romanian among the wooden tables and chairs in the tavern’s decor.

The story ties in nicely: Napoleon Zaglis is 73 years old and the fifth-generation owner of a place that dates back to 1840 – one of the oldest cafes in Greece, opened initially by his great-great-grandfather! He took it over in ’95, after giving up the corporate life in Athens, and added a six-room guesthouse for those who want to delve deeper into the Vlah mountain. He’s happy to sit and chat, so he puts on a vigorous, opening tsipouro, brings out some pies, crafts an omelet on the spot, and slams down a portokalopita (brilliant!). He twirls his white whiskers when he sees he’s posed and turns on the story tap. Then, out of the blue, he slips in a wedding song, from which, if you prick up your ears, you pick up the story of the sacrifices a man makes to take a beautiful woman as his wife, eventually even getting past the wicked mother-in-law. From above, from a cage, two canaries also sing, in their own language, gracefully accompanying their master.

Here is the real Greece; here are its charades from history and forever hardened in the mountains. Old Napoleon waves us off as we leave, and silence falls behind us again in the village, bothered by nothing in this mild autumn. We stop along the way for more photos of the villages dotted with hills and mountains that look painted. I had no idea Greece was so beautiful beyond its… coastal celebrity.

The evening winds down, and we end up, once again, at a cauldron party. This time, things are much more elaborate. Giorgos Polizos, from the village of Tsopelas, has set up a mini-amphitheater in his backyard. Not surprising since Polizos is a well-known maker of antique musical instruments. The man is like the modern Chinese; only he’s harking back to a bygone era. More precisely, he goes to museums, peeks at ancient instruments, and then reproduces them using materials you wouldn’t expect: turtle shells, cow intestines, bones, and so on. There are 17 models of musical instruments recreated by kir Polizos, some of which are on display in museums – two flutes, he tells us, are even in the Louvre.

Tonight, Giorgos Polizos is throwing a party for the ‘cauldron’ at which he is making his new tsipouro production, so the grill is fired up, the salad is being prepared, the tsipouro is flowing into tumblers, and the wine is also making its appearance, in flasks. But the icing on the cake is the presence of a rebetiko band.

Surely you’ve heard of bouzouki, traditional Greek music played on the lute-like instrument of the same name. In any Greek tavern, you can hear the bouzouki. Well, rebetiko (the term has Turkish roots and means rebellious, unruly) is the ancestor of bouzouki music. The musical genre fascinated Greece from the early 20th century until the 1950s. A kind of sadness and pain music that deals with themes of exile, loss of family, imprisonment, life on the streets, unrequited love, and death. In other words, blue heart music played on lute and guitar and sprung from the slums of Athens and other Greek cities between the two World Wars. Rebetiko is the sweet music that introduced the world to the bouzouki instrument, from which the eponymous genre was quickly born and made its mark on the modern art of Greek song.

Four strapping lads sit on the first step of the amphitheater (which I also discover its purpose on this occasion) and begin to sing their hearts out. At one point, Kir Polizos invites his wife to dance, and the show is complete; both swaying, sometimes faster, sometimes more tenderly, to the admiring applause of the audience gathered ad hoc, who knows from where? – friends, neighbors, guests, appetites, and desires. The evening is magical, the 147 cats in Polizos’s yard seem happy, and the Epirus of the Vlachs is also a master at delight.

Plaka, or how the perfect bridge looks like

You could write books about the stone bridges of the Balkans. Northern Greece is littered with stone bridges. In the Zagori region alone, there are over 160 examples, most built in the 18th and 19th centuries by local engineers. They are bridges that generally have between one and three arches (called kamares in Greek), and the largest of Epirus’ stone bridges is the Plaka Bridge in the town of the same name.

Plaka is a single-arch bridge built in 1866 by the Ottoman Sultan Abdülaziz on the Arachtos River to help improve trade relations between local communities. Between 1881 and 1912 (the year of the First Balkan War), it also served as the border between Greece and the Ottoman Empire, serving as one of the two official entrances to mainland Greece.

Unrepaired over the years, the bridge was destroyed on 1 February 2015 by a severe storm, during which a significant part of the arch and the east abutment collapsed into the river’s ford. Fortunately, thanks to the quick efforts of the authorities, the bridge was restored in 2020 and restored to its former condition and beauty.

The Plaka Bridge is the first stop on this new day as Achilles takes us to some of the natural beauty of Epirus. We walk for about five minutes along the Arachtos River, which I imagine raging and bloody. Now it’s quiet as a baby who’s sucked on a tit. A teenage cat follows behind us like a faithful dog, playing the playful guide. You can’t help posing her, at least, if you can’t give her the life of a queen.

The majestic bridge arches over the river, and I imagine it’s a faithful representation of the cat in a moment of fear or anger.

It looks impeccable and seems to “demand” to be posed from every angle because it looks like a shining diamond set on a landscape crown from which you can’t take your eyes.

After the photo session, we continued our epiphany to the Vikos canyon and stopped for a few minutes at the Stone Forest near the village of Monodendri. There are many stone forests in the world – the most famous is the one in Madagascar, the nearest – the one in Bulgaria – the results of nature’s playfulness. In fact, numerous limestone formations scattered over a vast area give the impression of rock trees, rising among the ‘real’ trees – in this case, maple and oak. A ‘picture’ created over thousands of years, during which winds, rains, and other weather phenomena have ‘sculpted’ the limestone into shape.

But the Stone Forest is just the beginning of what’s to come in this beautiful region of Epirus. Because the Vikos gorge/canyon/canyon (call it what you will) is one of the most beautiful mountain areas in Europe (and, dare I say it, the world). And not just because Vikos holds the world record for the deepest gorge – 1350 meters at its deepest stretch (which is why the locals call it the Grand Canyon… of Greece).

The fantastic Vikos canyon and the magnificent Papingo village

To get the geography completely straight (and so you know where to look for it because you have to visit it), Vikos is in the Zagori region of Epirus, in the northern Pindus Mountains, 30km north of Ioannina and about 40km from the Albanian border. The gorge is 12 km long (‘the core’, as the total length is 30 km) and can be covered in two or three stages: from Monodendri in the north to Vikos, from Monodendri in the south to Kipi, and from Vikos to Papingo.

Now, don’t imagine that I “hiked” it. Unfortunately (or fortunately), we arrived at the Beloi lookout point, fell in awe at the sight of the masterful landscape (which I’ll let you admire in the photos that don’t even half capture its grandeur), and then drove through it in Achilles’ car, with short breaks for pictures from various places.

Not having, therefore, the whole experience of walking the 12 kilometers, I found out, however, that there are a few targets in the Vikos Gorge that any mountain lover can put on their itinerary. From the Stone Forest, I mentioned above to the Vlach villages of Zagori (there are about 40 of them, and each one needed to have a church, a central square, and a plane tree) – which remained self-sufficient during the Ottoman rule and which delight with their traditional, grey-roofed houses, but also with the fact that a human being was reported in the area over 10,000 years ago. From the Rizario Handicraft Centre (in the village of Monodendri) to the monastery of Aghia Paraskevi (Saint Paraschiva – 15th century). From the historical bridges to the Vradeto stairs (which took 20 years to build in the early 18th century and connected the villages of Vradeto and Kapesovo over a distance of 3.5 km, up and down steep ascents and descents).

There is much to see in the Vikos Gorge region. We also stopped at the Rogovo natural pools, also called Ovires or Kolybithres, which would be ideal for visiting in summer. These pools were formed by the erosion of the flat limestone cliffs over which the Rogovo River flows. Small artificial dams along the river control the water level in the pools, so in summer, they become perfect bathing spots for locals and visitors alike.

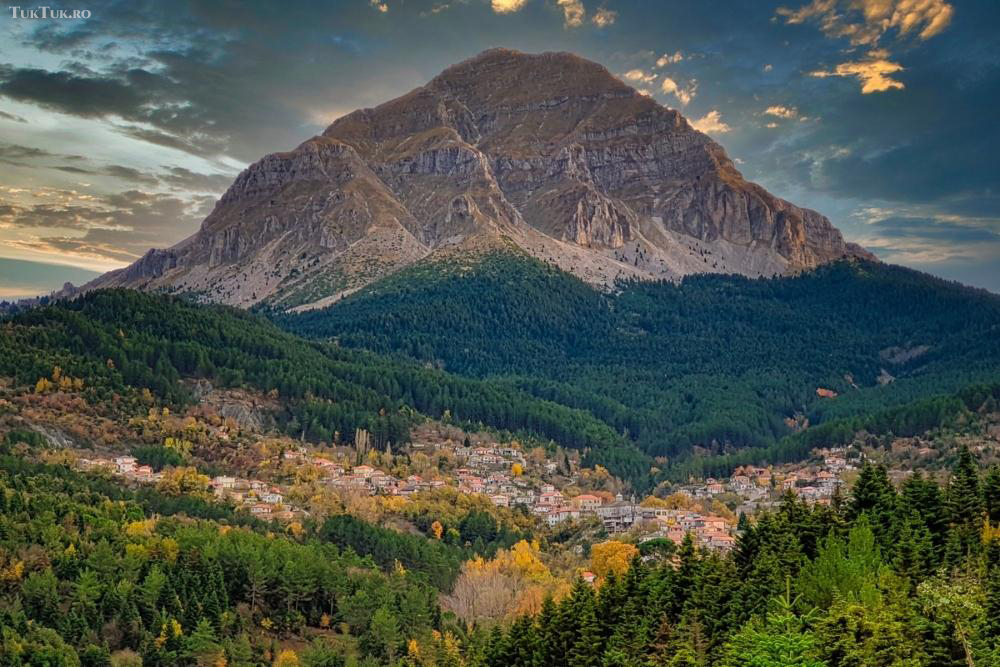

As Rogovo is near a jewel village in this region of Vikos-Aoos National Park, we stop at sunset to spend an hour in its quiet lanes. It’s Papingo (made up of two ‘parts’ – Megalo Papingo and Mikro Papinko, the big one and the small one), which lies at the foot of Mount Tymfi ‘shadows’ it with its peak Astraka (2436 meters).

Papingo, as far as I could see from it, left me in awe. The crowning beauty of this region of north-western Greece seems to have been drawn by a goddess full of grace whose destiny was to paint on the Earth. When you enter Papingo, you know you’re in an extraordinary place once you see the 18th-century Byzantine monastery of Saint Paraschiva (Agia Paraskevi).

The cobbled streets, the houses built in the same local architectural style, the fountains, other small Byzantine churches, the elementary school (one of the five Kallineia Schools founded in 1888 in Papingo the Great and the Little by Michael Anagnostopoulos, a famous teacher and human rights fighter from this region who died, incidentally, in Romania in 1906 while visiting our country), the guest houses, hotels, cafes, and terraces – all have a magical harmony, ready to delight you instantly.

In this fascinating rural heavens, I discover a micro-universe to match at Nikos Tsoumanis’s antique shop, which besides the thousands of objects gathered in a true homage to the past, has a wall full of liqueurs, of the most common and unusual fruits and plants, like a wizard with magic potions, ready to offer you the secret elixir to get you out of trouble or, who knows, on the contrary, to punish you for your deeds. I escaped with a tasting of pomegranate and peach liqueur and left Papingo, towards Ioannina, with the feeling that heaven is like happiness: it appears, in small doses, from time to time and from place to place.

Pin it!

You may also like: Northern Greece: a journey to Drama, the beloved region of the god Dionysus