Ready to embark on a journey through time? Step into the vibrant streets of Japan’s capital and discover the top 7 historic Edo-era landmarks in Tokyo that have stood the test of time. Immerse yourself in the rich tapestry of this bustling metropolis as we guide you through hidden alleys and winding streets, where ancient traditions still thrive.

Each landmark holds a captivating tale from Tokyo’s past, from the tranquil Hamarikyu Gardens to the majestic Senso-ji Temple. Delve into the city’s history at the Edo-Tokyo Museum, or pay your respects at the iconic Meiji Shrine. Feel the imperial grandeur at the Imperial Palace and savor the flavors of history at Tsukiji Fish Market. Finally, wander through the heart of old Tokyo in Asakusa. Get ready to explore Tokyo’s storied past and unlock the secrets of its Edo-era treasures. And if you don’t know where to stay in Tokyo, here is a guide for you!

Edo Castle (Imperial Palace)

Edo Castle, a pivotal symbol of Japan’s rich history, played a central role during the Edo period (1603-1868). Originally constructed in 1457 by Ōta Dōkan, a warrior-poet and Buddhist monk, the castle became the heart of Edo, the city that eventually evolved into modern Tokyo. Its strategic location at the eastern corner of Japan’s Kanto Plain made it a vital political and military center. The castle’s grandeur and expansive size, encompassing multiple moats, walls, and guardhouses, reflected the power and prestige of its occupants. As the residence and headquarters of the Tokugawa shoguns, Edo Castle was the de facto center of Japanese political power for over 260 years, marked by relative peace, isolationist foreign policy, and cultural flourishing.

Under Tokugawa Ieyasu, the founder of the Tokugawa shogunate, Edo Castle underwent significant expansions in the early 17th century, transforming it into one of the largest and most complex castle complexes in Japan. Its architecture was designed not only for defense but also to demonstrate the wealth and authority of the shogunate. The castle’s innermost circle of defense, the Honmaru (main circle), housed the main tower (tenshu) and the shogun’s residential palace. This area was strictly controlled and accessible only to the shogunate’s inner circle. The castle’s multiple concentric defense circles, including the Ninomaru (secondary circle) and Sannomaru (tertiary circle), were ingeniously designed to thwart enemy advances and protect the shogunate’s leadership.

One of the most distinctive features of Edo Castle was its impressive network of moats and stone walls. The moats, varying in size and depth, were an essential part of the castle’s defensive strategy. They deterred attacks and controlled access to the castle with carefully monitored bridges and gates. The stone walls, some of which still stand today, were feats of engineering, constructed without mortar yet incredibly durable. These defensive structures were complemented by various gates and guardhouses strategically placed to secure the castle against intruders.

Despite its formidable defenses and the shogunate’s long reign, Edo Castle never faced a significant military siege. Its role was more administrative and symbolic, serving as a hub for governance, culture, and diplomacy. The shoguns conducted official duties within its walls, met with daimyo (feudal lords), and engaged in elaborate rituals and ceremonies. The castle was also a cultural center, influencing arts, literature, and theater in Edo. Its presence shaped many aspects of Japanese culture that are still celebrated today.

Today, much of the original Edo Castle structure is gone, with only the stone foundations and some walls, gates, and moats remaining. The site is now part of the Tokyo Imperial Palace, the primary residence of the Emperor of Japan. The East Gardens of the Imperial Palace, where most of the Honmaru and some of the Ninomaru remain, are open to the public. These gardens allow visitors to appreciate the scale and historical significance of Edo Castle, offering a glimpse into the past glory of this remarkable fortress and its role in shaping Japanese history.

Kanda Shrine: known for the Shinto festivals

Kanda Shrine, known in Japanese as Kanda Myojin, is a Shinto shrine deeply woven into the historical and cultural fabric of Tokyo. Established in 730 AD, the shrine has a history spanning over a millennium. Originally located near the modern-day Otemachi area, it was moved to its present location in Kanda, close to Akihabara, during the Edo period. Kanda Shrine’s history is closely tied to the Tokugawa shogunate, as it was one of the most significant spiritual sites in Edo (now Tokyo). The shrine was revered not just by the common folk but also by the shogunate, and it played a pivotal role in the city’s spiritual life, offering protection and blessings to its inhabitants.

The architecture of Kanda Shrine is a striking example of traditional Japanese shrine design, featuring a vibrant red and gold color scheme that is typical of Shinto shrines. Over the centuries, the shrine has been rebuilt several times due to damage from fires, earthquakes, and war. The current main hall was reconstructed in the 1930s and stands as a testament to the resilience and enduring cultural significance of the shrine. The entrance to the shrine is marked by a massive torii gate, a typical feature of Shinto shrines, symbolizing the transition from the mundane to the sacred.

Kanda Shrine is perhaps best known for the Kanda Matsuri, one of Tokyo’s three great Shinto festivals, the Sanno Matsuri and the Sanja Matsuri. The Kanda Matsuri, which dates back to the early 17th century, is a biennial event in mid-May in odd-numbered years. The festival features a grand parade with hundreds of participants, including mikoshi (portable shrines) carriers, musicians, and dancers, traveling through central Tokyo. The procession historically included a route through Edo Castle, emphasizing the shrine’s connection to the shogunate. The festival’s energy, color, and history attract visitors from all over Japan, making it a vibrant and dynamic celebration of Tokyo’s cultural heritage.

Beyond its grand festivals, Kanda Shrine is a place of daily worship and spiritual significance for the local community. It enshrines three deities: Daikokuten, one of the Seven Lucky Gods in Japanese mythology, Ebisu, another god of fortune and prosperity, and Taira no Masakado, a revered samurai who is worshipped as a deity. These deities are believed to bring good luck, prosperity, and protection from misfortunes. The shrine is a popular spot for business owners and students to pray for success and good fortune, reflecting its continued relevance in the daily lives of Tokyo’s residents.

Today, Kanda Shrine is a cultural landmark in the heart of a rapidly modernizing Tokyo. Surrounded by the electric town of Akihabara, known for its electronics shops and otaku culture, the shrine offers a serene and spiritual contrast to the bustling city life. Its presence is a reminder of Tokyo’s rich history and traditions, serving as a bridge between the past and the present. Visitors to Kanda Shrine can experience this unique blend of ancient tradition and modern vibrancy, making it a must-visit destination for those looking to delve into the multifaceted cultural tapestry of Japan’s capital city.

Ryogoku: the Heartland of Sumo

Ryogoku, a neighborhood in the Sumida district of Tokyo, Japan, is steeped in history and is famously known as the heartland of sumo wrestling. The area’s association with sumo dates back to the Edo period (1603-1868), when the sport was highly popular among the Japanese population. Sumo wrestling evolved from a ceremonial ritual to a professional sport during this era, and Ryogoku became its epicenter. The neighborhood was strategically positioned near the Edo Castle, making it a convenient location for samurai and other spectators from the higher echelons of society to visit. Its proximity to the Sumida River also made it easily accessible for people from different parts of the city.

The centerpiece of Ryogoku’s sumo culture is the Ryogoku Kokugikan, the primary sumo hall in Tokyo, where major tournaments are held. First built in 1909, the Kokugikan has undergone several reconstructions, with the current building dating back to 1985. It can accommodate approximately 11,000 spectators and hosts three of the six annual Grand Sumo Tournaments (Honbasho). These tournaments are major events, drawing crowds from across Japan and worldwide. The energy inside the Kokugikan during these bouts is electric, with fans passionately cheering for their favorite wrestlers.

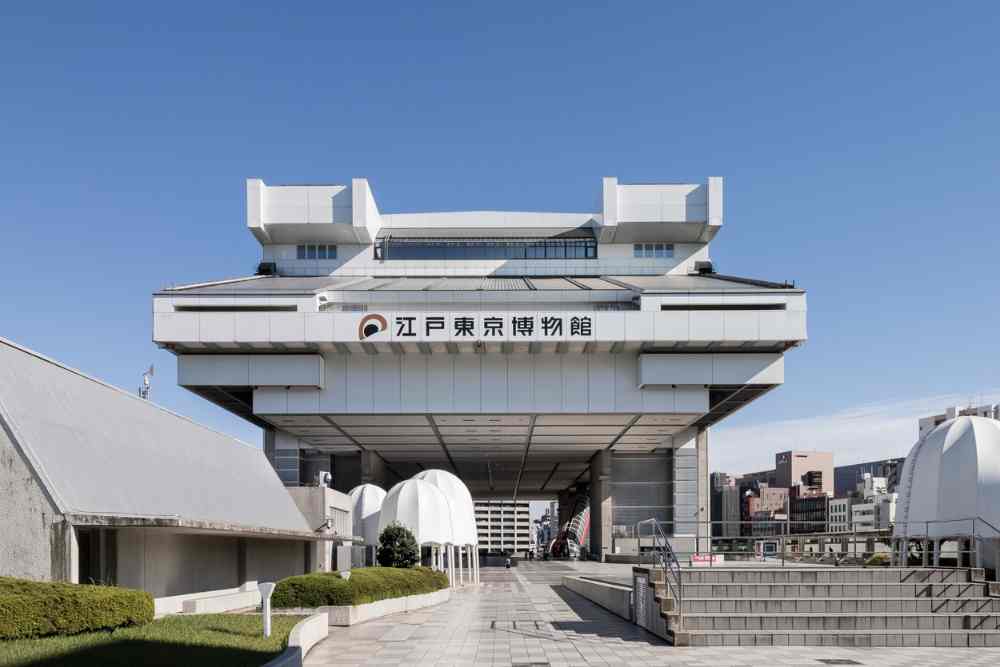

Ryogoku is not only about sumo; it’s also a district rich in history and culture. The neighborhood was heavily damaged during the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923 and again during World War II, but it has since been rebuilt and continues to be a vibrant part of Tokyo. One of its key historical sites is the Edo-Tokyo Museum, which opened in 1993. This museum offers a deep dive into Tokyo’s past, with exhibits that range from the Edo period to modern times. Its architecture, resembling an elevated warehouse, is a landmark in itself and symbolizes the elevated houses of the Edo period to prevent flooding.

Besides its historical and cultural significance, Ryogoku is also known for its culinary scene, particularly its chanko-nabe, a hearty stew commonly eaten by sumo wrestlers. This dish is a staple in local restaurants and is as much a part of the sumo culture as the sport itself. Chanko-nabe is traditionally made with a rich broth, various meats, and an assortment of vegetables, providing the necessary calories and nutrition to support the wrestlers’ rigorous training regimes. Dining at one of Ryogoku’s many chanko-nabe restaurants offers a unique opportunity to experience a part of sumo tradition.

Today, Ryogoku continues to be a vibrant and essential part of Tokyo’s cultural landscape, offering a unique blend of history, sport, and tradition. Its streets are lined with sumo stables, where visitors can sometimes see wrestlers in training. The neighborhood hosts various festivals and events throughout the year, celebrating its rich sumo heritage and inviting both locals and tourists to partake in its unique cultural offerings. Whether it’s witnessing the intense battles of sumo wrestlers, exploring the depths of Tokyo’s history, or savoring the local cuisine, Ryogoku offers an experience that is deeply rooted in Japanese tradition and is a must-visit for anyone looking to understand the multifaceted culture of Tokyo.

Hama-rikyu Gardens: serenity in the middle of Tokyo

Hama-rikyu Gardens, a serene oasis amidst the bustling cityscape of Tokyo, is a place where history and nature converge in harmonious beauty. Located at the mouth of the Sumida River, this public park was once a feudal lord’s private residence and duck hunting grounds during the Edo period (1603-1868). Later, it became a detached palace garden for the Tokugawa Shogunate, serving as a recreational space for the ruling elite. The gardens are a stunning example of traditional Japanese landscape design, featuring tidal ponds, meticulously manicured trees, and a variety of seasonal flowers that provide a colorful display throughout the year.

One of the most distinctive features of Hama-rikyu Gardens is its large seawater ponds, which are directly connected to Tokyo Bay. The water level in the ponds changes with the tides, a unique aspect that sets these gardens apart from other traditional Japanese gardens. This ingenious design, a hallmark of the sophisticated landscaping techniques of the Edo period, creates a dynamic relationship between the gardens and the natural rhythm of the sea. The largest of these ponds, Shioiri-no-ike, is home to a charming teahouse, Nakajima-no-ochaya, situated on a small island accessible via a bridge. Visitors can enjoy matcha (green tea) and Japanese sweets here, relishing the tranquil scenery that surrounds them.

The gardens are not only a celebration of natural beauty but also a showcase of Japan’s rich cultural history. They feature a diverse array of plants and trees, including pine, cherry, and ginkgo, which have been carefully cultivated over centuries. Each season brings its own charm: cherry blossoms in spring, irises in early summer, and vibrant autumn leaves. The layout of the gardens is designed to provide a different perspective at every turn, with walking trails leading visitors through various scenic spots, including a 300-year-old pine tree, meticulously trained to grow in a distinctive shape, and several historic duck hunting sites.

In addition to the natural and scenic attractions, Hama-rikyu Gardens also glimpse Japan’s feudal past. The remnants of the Tokugawa family’s former duck hunting lodges are still visible, reminding the gardens’ historical significance as a place of leisure and entertainment for the shogunate. Furthermore, the gardens’ location adjacent to the bustling Shiodome area highlights the contrast between Edo-era Tokyo and the modern metropolis. This juxtaposition allows visitors to contemplate the city’s evolution from a feudal society to a leading global capital.

In our days, Hama-rikyu Gardens stand as a testament to the endurance and adaptability of Japanese culture. They offer a peaceful retreat from the hectic pace of urban life, inviting visitors to unwind and reconnect with nature. The gardens are a place for relaxation and cultural education, where people can learn about traditional Japanese gardening techniques and the country’s history.

Edo-Tokyo Museum: Exploring the City’s History

[Later edit: closed until 2025 for renovation] When exploring Tokyo’s historic Edo-era landmarks, you should definitely visit the Edo-Tokyo Museum, where you can delve into the city’s captivating history. This museum offers a unique and immersive experience, allowing you to travel back in time and witness the transformation of Tokyo from the Edo period to the modern metropolis it is today.

As you step into the museum, you’ll be greeted by a stunning replica of the Nihonbashi Bridge, a symbol of Edo Tokyo. From there, you’ll embark on a journey through the city’s history, with exhibits showcasing the daily life, culture, and architecture of the Edo period. You’ll get to see intricate models of Edo-era buildings and explore recreated streets, giving you a glimpse into what life was like during that time.

One of the highlights of the museum is the Tokyo Zone, where you can witness the city’s evolution from the destruction caused by the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923 to its post-war reconstruction. Through interactive displays and multimedia presentations, you’ll gain a deep understanding of the city’s resilience and determination to rebuild.

The Edo-Tokyo Museum also offers a range of activities and workshops, allowing you to further immerse yourself in the city’s history. From traditional crafts to performances, there’s something for everyone to enjoy.

After exploring the museum, why not continue your journey into Tokyo’s history by visiting some of its other iconic landmarks? From the historic Asakusa district with its famous Senso-ji Temple, to the trendy shopping districts of Shibuya and Harajuku, Tokyo offers a wealth of experiences for history enthusiasts and shopaholics alike.

Yanaka: rich history in a modern city

Yanaka, nestled in the Taito district of Tokyo, Japan, is a neighborhood that exudes a unique charm, distinct from the high-paced, modernized parts of the city. Often referred to as part of “Shitamachi” – the traditional name for Tokyo’s historical downtown areas – Yanaka has a rich history that dates back to the Edo period (1603-1868). Unlike many parts of Tokyo, Yanaka was largely spared from the extensive damage of World War II bombings and the subsequent wave of urbanization.

This fortunate preservation has allowed Yanaka to retain a sense of old Tokyo, with its narrow lanes, traditional wooden houses, and a slower, more relaxed pace of life. The area offers a nostalgic glimpse into the past, starkly contrasting the skyscrapers and neon lights in other parts of the city.

One of Yanaka’s most notable characteristics is its abundance of temples and shrines, a legacy of its past as a temple district. During the Edo period, the Tokugawa shogunate relocated numerous temples to Yanaka and surrounding neighborhoods. This was part of a strategic plan to create a protective spiritual barrier against threats from the northeast. Today, visitors can explore these historic sites, which include the famous Yanaka Cemetery. This sprawling, serene space is not only a final resting place but also a beautiful park, known for its cherry blossoms in the spring and serving as a peaceful retreat from the urban hustle.

Yanaka Ginza, the neighborhood’s main shopping street, is a vibrant testament to the area’s community spirit and traditional way of life. This street, often bustling with locals and tourists alike, has small, independent shops, cafes, and eateries. Here, one can find an array of goods ranging from traditional crafts and local snacks to contemporary art and handcrafted jewelry. The street captures the essence of Yanaka’s charm – a blend of the old and the new, where traditional artisans and modern entrepreneurs coexist harmoniously. Walking through Yanaka Ginza, with its Showa-era (1926-1989) atmosphere, is like stepping back in time, starkly contrasting Tokyo’s more modern and commercialized districts.

Yanaka is also celebrated for its artistic and cultural scene. The neighborhood has become a haven for artists and creatives drawn to its tranquil atmosphere and historical backdrop. Numerous small art galleries, studios, and workshops, often housed in quaint, refurbished buildings, dot the area. This creative environment fosters a sense of community among local artists and attracts visitors interested in contemporary art and traditional Japanese crafts. The area’s artistic vibe is further enhanced by various events and festivals that take place throughout the year, showcasing the talents and works of local residents.

Today, Yanaka stands as a rare gem in Tokyo, a city known for its relentless modernization. It offers a peaceful escape and an opportunity to experience a different side of Japanese life. Visitors to Yanaka are invited to stroll its streets, explore its hidden alleys, and discover its rich cultural tapestry. From savoring traditional street food to engaging with local artisans, from wandering through historical sites to experiencing the area’s artistic offerings, Yanaka provides a unique, immersive journey into Tokyo’s past and present. This charming neighborhood remains a testament to the endurance of traditional Japanese culture and community spirit amidst the ever-changing urban landscape.

Asakusa: The Heart of Old Tokyo

Asakusa, a district in the Taito ward of Tokyo, Japan, is a vibrant neighborhood that seamlessly blends the traditional and the modern. Renowned for its historical atmosphere, Asakusa was once the entertainment hub of Tokyo during the Edo period (1603-1868). This era saw Asakusa develop into a bustling area focusing on kabuki theaters, sumo wrestling, and a thriving geisha culture. The district’s history is deeply intertwined with the common folk of Tokyo, as it was one of the few places where they could indulge in entertainment and leisure activities, making it a lively and popular destination.

The centerpiece of Asakusa is Senso-ji, Tokyo’s oldest temple, which is believed to have been founded in 628 AD. The temple is dedicated to Kannon, the Buddhist goddess of mercy, attracting millions of visitors yearly. The iconic Kaminarimon (“Thunder Gate”) serves as the entrance to Senso-ji, featuring a giant red lantern that symbolizes Asakusa and Tokyo. Beyond the gate lies Nakamise-dori, a shopping street with stalls selling traditional Japanese crafts, snacks, and souvenirs. This bustling street leads to the temple’s second gate, the Hozomon, and finally to the main hall, where visitors can experience traditional Buddhist practices and rituals.

Besides its religious significance, Asakusa is also known for its cultural and festive atmosphere. The Sanja Matsuri, one of Tokyo’s three great Shinto festivals, occurs here every May. This lively festival, centered around Asakusa Shrine (a Shinto shrine adjacent to Senso-ji), features portable shrines (mikoshi) paraded through the streets, traditional music, and dance performances. The festival and other cultural events held in Asakusa throughout the year showcase the area’s deep-rooted connection to Japanese traditions and its enduring community spirit.

In contrast to its historical and cultural sites, Asakusa has also embraced modernity. The Tokyo Skytree, the world’s tallest tower, is located nearby and offers breathtaking city views from its observation decks. The area around the Skytree includes a modern shopping complex, aquarium, and various dining options, blending the new with the old in a distinctly Tokyo fashion. This juxtaposition of the traditional and the contemporary is a defining characteristic of Asakusa, making it a unique destination within Tokyo.

Today, Asakusa remains a popular tourist destination, offering a glimpse into Tokyo’s past while still being vibrant and relevant. Visitors can enjoy rickshaw rides through the historic streets, sample traditional foods like tempura and ningyo-yaki (a sweet cake), and explore the many shops and stalls that line the district’s alleys. The blend of history, culture, religion, and modernity makes Asakusa a microcosm of Tokyo’s broader appeal, attracting tourists and locals who wish to reconnect with their cultural heritage. Whether exploring ancient temples, participating in traditional festivals, or enjoying modern amenities, Asakusa offers a rich, multifaceted experience to all who visit.

Final Theoughts About Edo-Era Landmarks in Tokyo

As your journey through Tokyo’s historic Edo-era landmarks comes to a close, you will have experienced the captivating allure of this vibrant city’s past. From the tranquil Hamarikyu Gardens to the majestic Imperial Palace, each site reveals a glimpse of Tokyo’s rich history. As you walk the hidden alleys of Asakusa and soak in the serenity of Senso-ji Temple, you will truly understand the allure of this bygone era. So lace up your walking shoes and prepare to be transported back in time on this remarkable exploration of Tokyo’s historic treasures.

Note this out of date.

The Edo-Tokyo museum is closed until 2025 for remodeling, the Tsukiji Fish Market closed in October 2019 replaced by the Toyosu Market, however the cool outer market is still going, plus the market is not from Edo Period but the Taisho Period some 50 years after the Edo Period ended. And of course the Meiji Shrine is also from the Taisho Period. There’s more but I’ll stop there.

Thank you for the details! We refurbished the article with more accurate information.