As soon as hearing of Morocco, many people instantly run their thoughts to Casablanca. And to the famous film with Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman, which, since 1942, continues to squeeze the tears of romantic cinephiles (although not even one scene was filmed here). Anyway, I know for sure that a visit to Morocco is poorer without a trip to Casablanca. Keeping in mind that Casablanca, Morocco, flights are pretty cheap if you come from Europe.

I’m heading to Casablanca after I had a real surprise visiting the capital Rabat, even on the run. There are 87 kilometers between the two cities, made on the Atlantic coast in an hour of highway travel. Morocco is not crowded with highways but has built the network it needs to connect its main cities and areas. In other words, although the distances between tourist places are long, you ‘fix’ them decently. In the following we’ll see how to spend a day in Casablanca. Or more.

As its name suggests, Casablanca is “the white city” of Morocco. Marrakesh is “the red city”. Between white and red, Morocco experiences its joys and hopes, defining its culture and spirit from the lifeblood of a long history. Casablanca – founded in the 7th century and called, at first, Anfa – was one of the most important Berber cities in the Kingdom of Barghawata in the middle of the 8th century. In the 14th century, it had already become a port of strategic importance, and a century later, the port had been conquered by pirates who felt here more like Abraham.

But that’s before the Portuguese came, who broke up their party and blew up their parrots. In 1755, Casablanca was destroyed by an earthquake. But the bounty of Sultan Mohammed ben Abdallah brought him back to life, waiting for the 20th century and the invasion of the French, who colonized the city and, obviously, turned it into a strategic port in the Second World War. Since 1955, along with the entire country, the city found the peace offered by gaining independence.

The first impression from Casablanca is… slightly dusty. The white buildings have nothing spectacular and seem swallowed by nonacademic boredom. I find out quickly that Casablanca is the ugliest city in Morocco. Well, as far as a Moroccan city can be ugly. But this “ugliness” is given by two things: the first, and most importantly, is that the white city is the country’s economic capital. Second, it’s in an effervescent construction.

This is where are gathered all the major institutions, companies, industries, banks, and other such cogs, which set a country’s economy in motion. No wonder: Casablanca is the largest city of Morocco (and the entire Maghreb), with 3.5 million inhabitants, double the size of Rabat. And with a port through which goods weigh 21.3 million tons a year. Casablanca is the city where Moroccan money is made, “drawn” from French General Louis Hubert Gonzalve Lyautey. At the beginning of the 20th century, this is the one who, when Morocco had entered under the French protectorate, hired his countryman, architect Henri Prost, to “redraw” the city so that it would become the economic center of the colony.

That is how Casablanca looks more like a European city at the moment. It was the first sensation when I stepped on the wide boulevards, bordered by buildings – let us say them – modern, in a city woven from place to place by parks, squares and fountains, by bars and restaurants, but conveying contradictory feelings.

Without a doubt, Casablanca is a cosmopolitan city, which inspires its vibe from Europe. The center is way over the suburbs, where things don’t seem quite right. But the art-deco architecture in the downtown leaves no room for interpretation.

I spent two days in Casablanca at a hotel on Boulevard de Paris, which boasted four stars, probably picked from the sky, of the falling ones. Nothing entitled it to stars. But looking at the boulevard at the height of the 7th floor, through a dirty thermopane, in front of a fallen curtain, I had the revelation that I am in a place that does not deserve its crutches: Casablanca whispered in my ear, at the evening clock, a story with pistachios. (anyway, if you’re looking for accommodation, try the Casablanca Morocco Four Seasons hotel).

So I took my backpack and went sideways, stopping in Mohammed V Square to admire the colorful fountain game, a small-scale imitation of the famous singing fountain in Barcelona. An example of art deco architecture of the 20s combines modernism and tradition, on the edges of which are boasted some important buildings, built after the First World War: the Consulate of France, the Prefecture, the Post, and the National Bank.

Nearby, the Arab League Park is the largest “green” area of the city, a gathering place for young people and the loser, but also a good pretext for the shops, bars, and restaurants that take place in the west and south-west of the park.

Hassan II Mosque is Casablanca’s pride

Since the town of Casablanca positions itself as a commercial and economic center, the tourism industry is almost non-existent. And yet, there was someone who thought that this city should also be attractive to the tourists. That it should have a place, at least one, that would become “iconic,” which would define it, beyond the useless association with Michael Curtiz’s film.

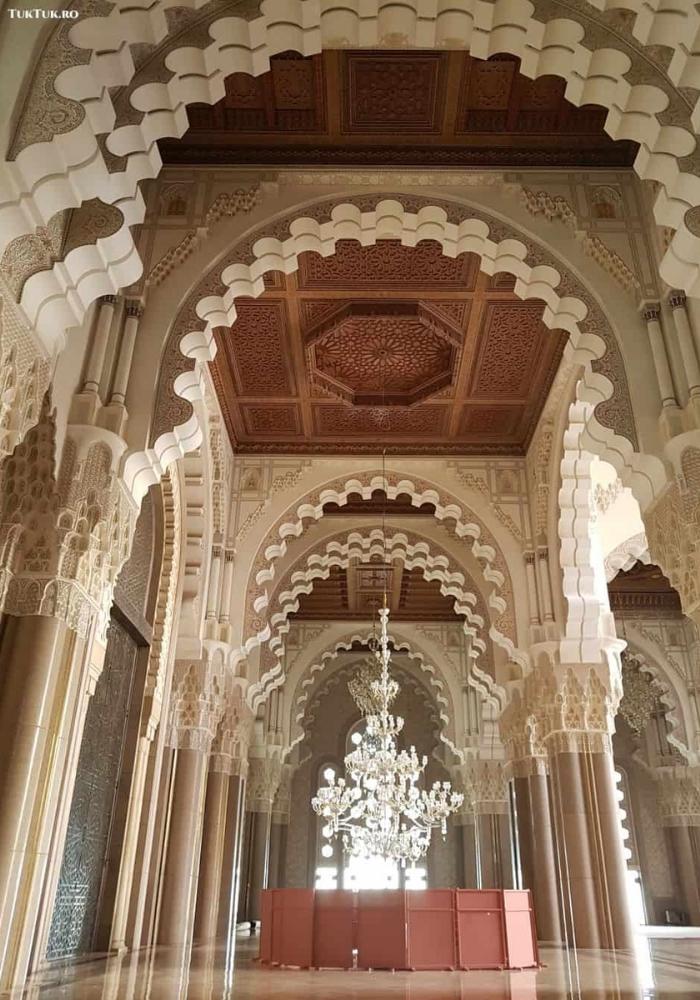

That “someone” was King Hassan II. To celebrate his 60th birthday, he “ordered” the construction of a mosque bearing its name from public funds. In 1993, the Hassan II mosque appeared, a real work of art by the French architect Michel Pinseau, raised over the ocean on a rocky promontory, proudly showcasing the 210-meter tower, the highest minaret in the world. A laser beam points the direction to Mecca from the top of it.

Hassan II Mosque is truly impressive. And, somewhere, it’s exactly the balance that Casablanca needed to live spiritually. It’s just that today’s miracle didn’t come without a controversial history. Most of the 750 million dollars that went down the water of Allah were donated by the Moroccan people. Every Moroccan family was obliged to take part with a minimum sum in the mosque’s construction in exchange for a certificate of “donor.” But with a happy ending.

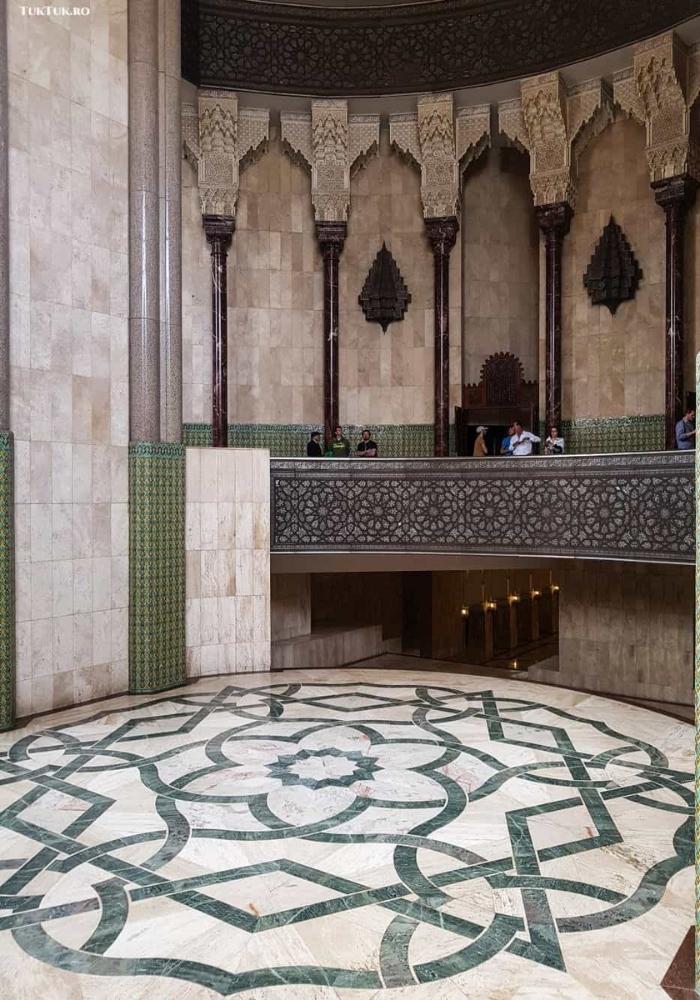

Six thousand workers and artists worked for five years to complete the masterpiece that can accommodate 80,000 people in the outer perimeter and 25,000 in the inner. All the materials used in its construction – marble from Agadir, granite from Tafraoute, cedar from the Atlas Mountains – are indigenous, except for the chandeliers and stained glass windows brought from Italy.

The mosque is an architectural delight that overwhelms you with its greatness and beauty since entering the inner courtyard. And once I walked inside, I was fascinated by two things. The first is that if you’re a Muslim and you come to pray here, you can do it in this enormous, exceptionally decorated prayer room with a beautiful view of the Atlantic Ocean in front of you.

The second is the retractable roof (weighing 1100 tons), through which the sun flows its heat, magically illuminating the interior of the mosque. I was lucky to catch it open and to attend his closing, enjoying the view of the minaret from the inside, in an ad hoc show, 5 minutes, absolutely remarkable. It is just one of the amenities indicating the mosque’s advanced degree of technology, along with the heat in the floor, electric doors, an underground parking lot, and the fact that it was designed to withstand corrosion and earthquakes.

Therefore, non-Muslim visitors can enter the mosque (a privilege, because it is the only mosque in Morocco that allows this) only with a guided tour, in a language of international circulation, which takes about an hour. Enough time to admire its monumental main hall, arcades, and columns, decorated with complex patterns, the women’s prayer room, Turkish-style baths, and the cellars in the cleaning room.

If we take it practically, Casablanca deserves to be visited mainly for the Hassan II Mosque. All the other things fall in front of this imposing monument. And even if, let’s say, The Corniche is the area where you can walk, you can jog or relax in front of an orange juice (by the way, in Morocco you’ll find one of the best orange freshes worldwide) or a mint tea (is it necessary to say that in Morocco you get one of the best mint teas in the world?), the fact that it builds a lot somehow bothers the atmosphere, making you think that probably in a few years Casablanca will look better.

The fake Rick’s Cafe from the Casablanca movie

As we know, and as I said above, Casablanca is a famous city primarily due to the homonymous film. Not many people know that not even a scene from Casablanca was filmed here. Moreover, all the scenes from the movie in question were realized at the Warner Bros studios in Hollywood, except for the scene at the airport.

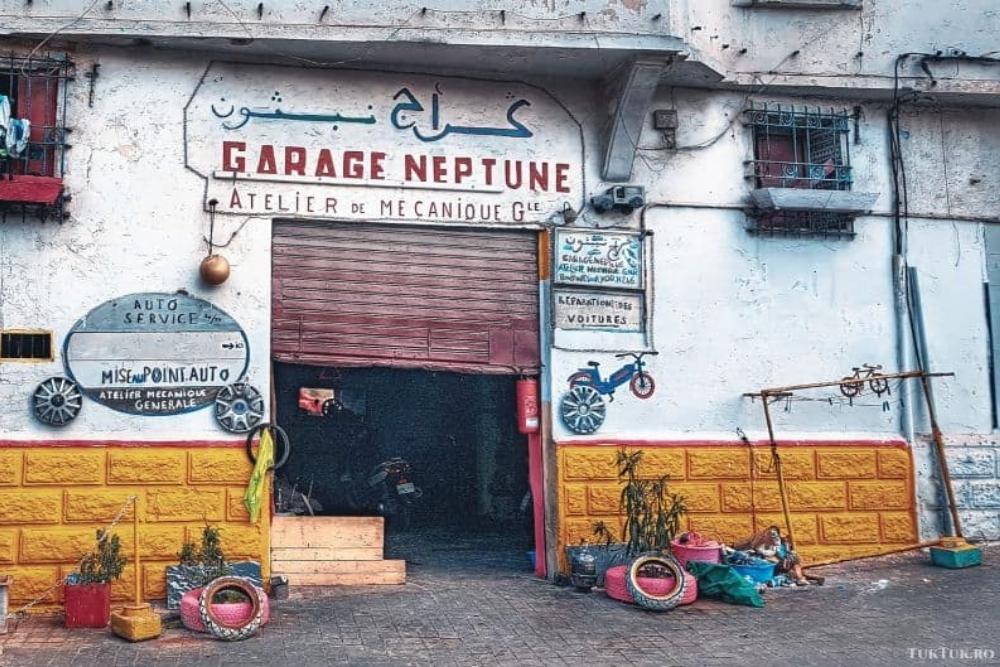

And yet, there had to be in Casablanca the famous Rick’s Café who defined production to a large extent. The “fake” cafe was opened in 2004, belongs to a former American diplomat, and tries to recreate the atmosphere in the film. I stopped here, for a “tourist” photo but, to be honest, I was rather impressed with how it looked the car service next to the cafe. From what I’ve read, however, it seems worth crossing the threshold: the menu is based on fresh fish and Moroccan and French dishes, a pianist sings As time goes by and upstairs running, in the loop, you guessed: the Casablanca movie.

Azemmour and El Jadida, the Portuguese ‘contribution’

During a quick tour of the neighborhoods in Casablanca, I noticed the beauty of a neighborhood with plenty of luxury villas and the Catholic Cathedral (Sacre Coeur), built by the French in 1930, which amazes you through architecture but also the immaculate white. Then, further out, on the ocean coast, to two attractive minor destinations: Azemmour and El Jadida.

Azemmour is an hour away from Casablanca, on the banks of the river Oum Er-Rbia, and the primary valence of this charming and quiet town, adulterated by many artists (especially painters), is the beach. If you’re a surfing fan or kitesurfing fan and want to fulfill your passion in Morocco, Azemmour is one of the most suitable places. If not, you can walk through the medina of this city founded in 1513 by the Portuguese.

However, even more interesting is El Jadida, which boasts of being the only non-Moorish city in Morocco. And very close to Azemmour. In 1506, the Portuguese built a fortress here to protect their caravans, naming it Mazagan. It became one of the country’s most important shopping centers in a short time.

Sultan Sidi Mohammed ben Abdallah disagreed with the presence of the Portuguese and besieged the fortress in 1769. He conquered it, but the Portuguese blew it up then disappeared. The new inhabitants preferred to live in the new city, so the citadel remained in ruins until the 19th century when Sultan Abd er-Rahman relocated some of the Jews of Azemmour to the old Magazan and renamed the city El-Jadida (“The New One,” in Arabic). In an atmosphere of friendship and tolerance, the Jews lived here, mixing with the Arabs without having the mellah (well-defined Jewish quarter).

El Jadida was a pleasant surprise. I took a walk through the medina. I admired the Assumption church, with its Gothic architecture. I visited the Portuguese tanks, and on the latter, maybe I should stop a little more because the place is exciting and equally bizarre.

So, before El Jadida regained possession of the Moroccans, the Portuguese had fun on these lands for about 250 years, making Mazagan (they called him Mazagao) and his fortress sort of a holiday village, which they equipped with various constructions, more or less beautiful: Christian churches, a synagogue, a communal oven and, la creme de la creme, these cisterns (1514) that served Orson Welles perfectly for his version of Othello, the great actor and director filming here the scene between Cassio and Roderigo.

The place was originally built as a warehouse, then it was turned into a weapons room and ended up as a water tank. The atmosphere inside brings the one from a place where you can easily film a horror production: bolted columns are overrun by dampness. The light penetrates through an “eye” in the middle of the room, where a basin discharges, making the water puddle around. The echo comes to complement this sinister yet fascinating underground landscape.

El Jadida is a poem of Lusitan verse, colored and sweet as a pasteis de nata. Of course, in the end, it enchants you with its fine beaches, promising unforgettable moments to all those who love water games.

You may also like: 10 things to do and see in Marrakech, the red city of Morocco